Alfred Hitchcock Presents

Written by Victoria Thomas (@Miss_Vickums)

America was increasingly strange place in 1955. The afterglow of the Allied victory quickly faded as new international anxieties surfaced. Although Russia had been a powerful cooperative force in crushing the Axis, dealings between the superpowers quickly cooled, leading author George Orwell to coin the term “Cold War.” While tensions between Russia and the U.S. seemed to be about the space race, the troubles ran much deeper. Americans took to building fallout shelters beneath the emerald-green lawns of their new cookie-cutter suburban homes, made affordable by the G.I. Bill to returning American servicemen.

Fears of direct nuclear attack and insidious Communist takeover permeated the American psyche. And these fears permeated the arts, including mid-century television programming. Fantasy and scifi became popular genres, with screwball plots of alien invaders standing in as thinly disguised metaphors for Soviet mind-control.

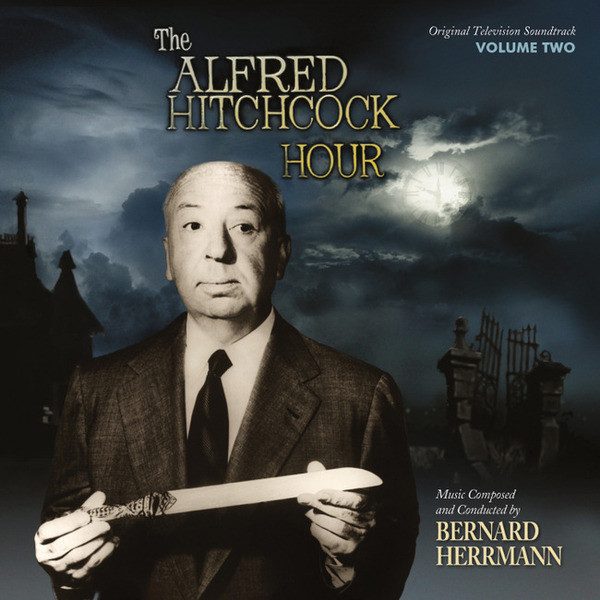

More droll, dry, and witty is Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the director’s classically British take on an unsettled and unsettling world. Hitchcock helmed the long-running American television anthology series which aired on CBS and NBC between 1955 and 1965, renamed The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1962. It’s a sophisticated though often campy mash-up of dramas, thrillers, and mysteries. The stories are stingingly bitter bon-bons, sweetly, neatly structured, impossible to resist and packed with ugly twists, usually blackmail and deceit about wealth or sex, often made hilarious by mistaken identity. Many episodes deliver moral lessons along the lines of a Greek myth, while others are simply mean-spirited for the sheer wickedness of it.

Hitchcock was a lifelong student and observer of human pettiness and frailty. Typically, an episode involves a selfish character who is foiled by some form of selfishness itself, with storyline that culminate in a Guy de Maupassant-like payoff. was able to attract top-drawer talent of the time, including Ray Bradbury as a collaborator who wrote episode 20, “And So Died Riabouchinska.” In this especially eerie episode, Claude Rains portrays a ventriloquist fixated on his female dummy, Riabouchinska. Rains’ character has been accused of murdering a juggler. The dummy becomes animated without benefit of her puppeteer and confides in a detective played by Charles Bronson that her ventriloquist-lover is indeed guilty, and that the murder was committed because the juggler planned to extort the human-puppet duo regarding their bizarre affair. She explains that she can no longer love him, and then falls silent, no more than a heap of painted wood. Audiences love the fact that the murderer’s lips are sealed, but that an inanimate object finds her voice to expose the truth.

Setting the stage for “The Twilight Zone” and other series which presented the possibility of the paranormal, Hitchcock’s content often embraced some aspect of the surreal and supernatural. When the character is sympathetic — which is generally not the case — the otherworldly element is simply poignant. In episode 102, called “The Foghorn,” a woman is haunted by the sound of a foghorn. Exactly why this sound bothers her is fuzzy; her recall is indistinct. Gradually, she pieces together her memory of her affair with a married man who was killed at sea when a liner crashed into their small boat in the fog. To the woman, whose name is Lucia, this tragedy seems only days-old, when in fact it occurred a half-century earlier, speaking to the power of human guilt and denial.

Hitchcock played his American audiences with consummate skill, knowing full well that television was not theatre, and knowing that Kansas was not London. With these realizations firmly in place, the calendar of episodes never erred too far into the esoteric. In the same season as “The Foghorn,” a mere four weeks later, domestic farce at its most broad kept the series comfortably middle-brow. Episode 106 called “Lamb to the Slaughter” tells the story of a pregnant woman who bludgeons her cheating husband to death with a frozen leg of lamb. The woman scorned simply puts the murder-weapon in the oven to roast, and serves it to the police who come to investigate the crime scene.

Some of the best episodes offer cruelly unflinching insights into the shallowness of human nature, served up with a comic-Gothic spin reminiscent of the short stories of Southern author Flannery O’Connor. In episode 100, called “The Return of the Hero,” two veterans are returning from war. One has lost a leg during the battle. One of the men phones his well-to-do family to see if they can accommodate a disabled man, and they refuse to offer that kindness. And both men then continue on their journey, since the man who made the call to his family is in fact the one who has lost his leg. His companion is intact.

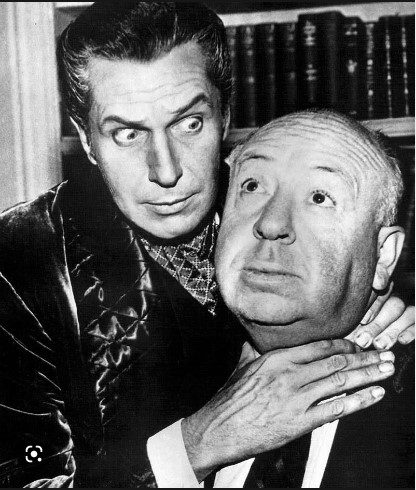

Audiences still ripple with excitement at Hitchcock’s ghoulish sense of the macabre, present in many episodes including number 81, titled “The Perfect Crime.” In this naughty bit of noir starring Vincent Price as a treacherous, two-timing detective who bends the truth for his own benefit. Price’s character, named Charles Courtney, strangles a lawyer who threatens to expose the fact that his incorrect analysis of a crime led to the punishment of the wrong man. Courtney uses the body of the murdered lawyer as a sculpting medium to create a ceramic trophy honoring the “perfect crime.” But, as is often the case in Hitchcock, the truth surfaces in a surprising way: a maid accidentally breaks the trophy when cleaning, and bits of gold from the victim’s teeth embedded in the ceramic reveal that Charles Courtney is indeed a killer.

It would be saccharine to claim that justice always triumphs in the twisted, twee world of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.” Indeed, some of the action suggests otherwise — some villains seem to get away with murder, literally. But to bring the episode to absolute closure, Hitchcock gave a typically thick-tongued, steady-eyed postscript (more like a post-mortem) at the end following the action, assuring the audience that goodness in some form, however grotesque, had prevailed against all odds.

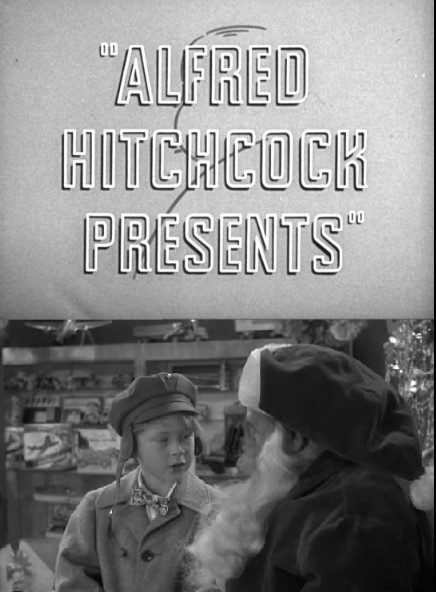

Occasionally, Hitch reveals a soft side, perhaps to please sponsors and attract advertisers. For example, a 1955 episode, number 12 in season one called “Santa Claus and the Tenth Avenue Kid,” stars veteran actor Barry Fitzgerald as an ex-con department store employee who steals a toy as a Christmas gift for a poor child. Fitzgerald’s character is caught by the police, but his parole officer has the charges dropped. Awwww. Hitchcock allows these moments of Disney-like sentimentality only rarely, and one suspects begrudgingly.

Notable actors, many very early in their careers, gave the series scintillating mid-century star-power:

Vincent Price, Ed Begley, James Caan and Robert Duvall (who went on to star together in “The Godfather, Part 1”, as well as appearing separately in numerous high-profile film projects. Tony Randall and Jack Klugman (Felix and Oscar in the TV version of “The Odd Couple”), Lee Majors (“The Million-Dollar Man”), James Farentino, David Carradine (“Kung Fu”), Peter Fonda, James Mason, Clint Eastwood (“Rawhide”), Steven McQueen (both Eastwood and McQueen appear in episode 39, titled “Human Interest Story,” 1959), Robert Redford, Jayne Mansfield, Robert Morse (“Mad Men”), and many more than we have space to list!

In the late 50s and early 1960s, most of the above were fledgling actors, and Hitchcock’s venue launched them into success on both the small and large screens. Many had extensive background in live theatre, but television made them household names. And Hitch’s remarkable dramatic vehicle also provided a fresh context for Hollywood names that had first been established in cinema decades before (Fay Wray who appeared in the original “King Kong,” Peter Lorre, Gloria Swanson, Lillian Gish, Bette Davis, Gilbert Roland, James Mason, Vincent Price, Hermione Gingold, Ray Milland, Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Keenan Wynn). Hitchcock also cast his daughter, Pat, in minor roles throughout the series.

A character that every episode has in common is the sensation of the grotesque itself. The word “grotesque” arises from the word “grotto.” This curious term finds its origin in classical Greece, where orderly beauty was held to be synonymous with moral goodness. It was the Hellenic culture at its height which gave us the Golden Mean or the Golden Ratio, a mathematical equation which makes itself evident in nearly everything that people in the West find beautiful, from well-balanced facial features to the sacred geometry of a temple. The reason that the Golden Mean resonates so easily, even beyond the West, is that this equation in inherent in many natural forms, beginning with the Fibonacci spiral present in a snail-shell’s whorl, or the coil of an unfurling fern frond.

In Greek society, there was also a subculture which did not conform to the Athenian ideal. The latter was the world of the grotto, a place of more primordial rituals and mysteries that strayed far from the rigor of Apollonian beauty. In the grotto, the Golden Mean was not even a consideration. The proportions of the ritual space and the objects in it were created to trigger feelings of discord and disorientation rather than stability and serenity. And rather than striving for the clear daylight of the supremely rational, visitors to the grottos devoted themselves to Dionysus, Pan, and even murkier entities in search of oblivion.

Hitchcock summoned this sense of the grotesque as something slimy and slippery that lurks and darts beneath the seemingly well-ordered surface of everyday life. Hitchcock’s work, including his films, allude to the presence of ordinary evil, what some would call the noonday devil. In “The Birds,” for example, there is little explanation for the mysterious avian mayhem that takes the lives of innocent people in the quaint, small town of Bodega Bay. Other than quite-normal sexual tension and flirtation, the characters are hardly sinister, and yet they become the victims of an unprovoked attack which seems protean, as if rising from the most primal energy of the life-force itself– a force which Hitchcock clearly believes is not entirely benevolent.

In the abbreviated format of his television series, the presence of this grotesque force is by necessity a bit less subtle and a bit less nuanced, and so Hitchcock introduces the problem of evil and its resolution in a more literal way. It begins with the portly and menacing appearance of Hitchcock himself. The series is well-known for its title sequence, set to the lurching strains of Charles Gounod’s “Funeral March of a Marionette.” The score, which pitches and rolls like a flimsy craft on a harsh sea, accompanies a deft caricature of Hitchcock onscreen, a line drawing self-portrait created by the director himself. The man himself appears as a bloated silhouette, a self-important dirigible, then walks to center stage to address the camera with an unsmiling greeting: “Good evening.”

Hitchcock is known for his use of editing and camera movement to mimic a person’s gaze, thus making the viewer a voyeur. This quality adds an element of salaciousness to the action. Many film scholars, notably Laura Mulvey, take Hitchcock to task for what she termed the “male gaze,” regarding women as objects of both desire and scorn. Roger Ebert wrote in 1966: “They were blonde. They were icy and remote. They were imprisoned in costumes that subtly combined fashion with fetishism. They mesmerized the men, who often had physical or psychological handicaps. Sooner or later, every Hitchcock woman was humiliated.”

This element of perversity permeates the master’s work. Like King Henry VIII, Hitchcock’s persona was one of rampant corruption and sensual decadence. His bulbous flesh sagged, his belly entering the viewfinder as a separate entity, the plush bulk of his cheeks muffling his speech. His weight became so out of control that insurers denied him coverage, in spite of his fame.

Hitchcock was a man of unsavory appetites. Tippi Hedren, the iciest of Hitchcock’s blondes, revealed in her memoir that she was fending off more than psychotic crows during the making of “The Birds.” After spurning his advances, which ranged from groping to full-body tackle, in retaliation Hitchcock deliberately allowed the actress to be injured by live birds used on the set. He then blocked Universal Studios from submitting her performance for Oscar consideration, and later refused to allow her to work with other directors. Hitchcock even engineered a connecting door between his office and Hedren’s dressing room, meaning that she surrendered any sense of personal privacy. After “The Birds,” Hedren’s next film for Hitchcock was “Marnie,” in which her character is raped — a scene which she believes was a message to her from the thwarted director.

Hollywood runs on dirty laundry and gossip, and so of course fans of Hitchcock prefer to concentrate on the genius of the man’s art. Hitchcock’s formidable intellect and superb technique make this entirely possible. And yet it is the lip-smacking suggestion of personal depravity in the psyche of the director himself that makes us feel a little dirty after watching his work — and keeps us coming back for more, decade after decade.

This review was written by Victoria Thomas (@Miss_Vickums), a Bronx-born pop culture writer who now lives in Los Angeles. She is the author of Hollywood’s Latin Lovers: Men Who Made the Screen Smolder (St. martin’s Press/Angel City Press) and contributes to several arts journals.