WHO KNEW?

by Victoria Thomas (@Miss_Vickums)

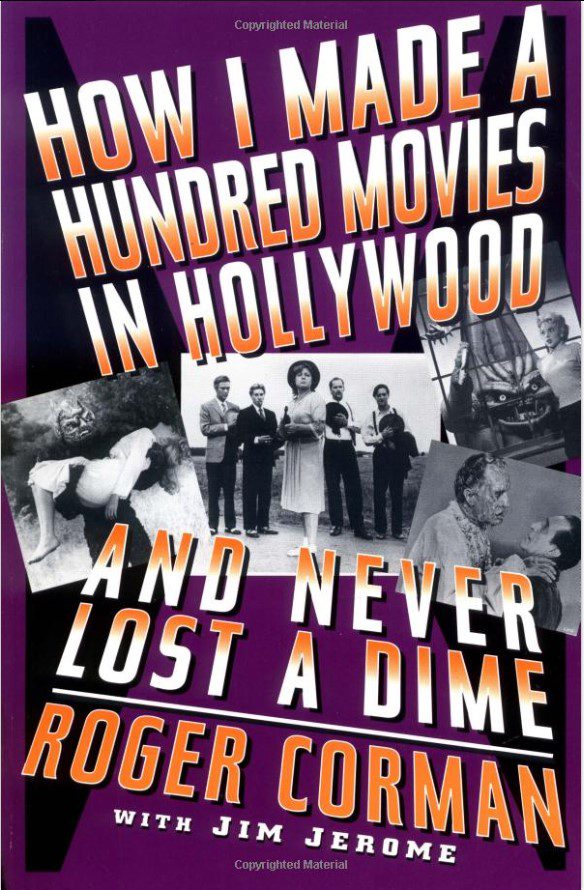

In his 1990 biography, “How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime” Corman wrote: “My film budgets have always been notoriously lean, while the waste and excess built into the major studios’ productions have tended to appall me.”

Corman’s attitude is quintessentially American: brash, irreverent, practical, with no use for the rear-view mirror, and no room for pretense. His credits are staggering: 56 for directing, and 412 production credits at last count. Corman was also willing to work as an uncredited producer or executive producer, and early on even worked for free, happy to apprentice and learn on the job. Among his most defining accomplishments: “The Fast and the Furious,” (1954), which was only Corman’s second feature.

High-minded film critics scoffed, and the crowds clamored for more. A scant decade later in 1964, Corman became the youngest filmmaker to be honored with a retrospective at the Cinematheque Francaise. Another followed at the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art, and Corman was awarded an Honorary Academy Award in 2009.

By 1960, Corman was viewed as an upstart, along the lines of a low-rent Spielberg or an even more shameless Tarantino. His sprawling list of unlikely successes began in 1960, with a campy horror quickie he shot in 2 ½ days, with an unknown in the lead role. The film: “The Little Shop of Horrors.” The mystery man: a young Jack Nicholson. Who knew?

Perhaps the most telling tribute to Corman’s DIY genius is the enduring legacy of “The Fast and the Furious” which, although it was only the second feature produced by Corman, has spawned a new generation of lucrative imitators. Corman wrote the story and shot the picture in 10 days. He persuaded a local Jaguar dealership to provide the omnipresent racing cars, and even got behind the wheel of a Jag XK120 himself for a few of the film’s more heart-revving drag race scenes.

Corman shrewdly decided to release the film via a then-new distribution company, American Releasing Corporation (ARC) versus Columbia, Allied and Republic studios, all of which had expressed interest. Corman’s reasoning was that as an independent, he’d be doomed working with the big studios, since the return on his investment would take years. Instead, he scored a negotiation with ARC: he’d do three films for them on the condition that they return his investment – a mere $60,000 in the case of “The Fast and the Furious,” released under Corman’s Palo Alto production company title.

Even though “The Fast and the Furious” often played at the bottom of a twin bill as a B-feature, the film embedded itself in the psyche of American filmgoers like an unshakable alien virus in one of Corman’s lesser classics. “The Fast and the Furious” represents the sacraments of Corman filmmaking: rock-bottom budget, a hard-scrabble cast, plenty of screeching tires and axle-snapping tumbles off highways, high-impact crashes, a con with a heart of gold, a jail-break, a criminal case of mistaken identity involving a wrongly accused truck driver, a nosy local in a coffeeshop who blows the whistle on the fleeing protagonist, and the tough-talking blonde and her brand-new Jag that the accused killer kidnaps and holds hostage in his attempt to reach Mexico and give the coppers the slip.

Giving the already gritty narrative even more edge is the fact that the truck driver Frank (played by John Ireland, who also co-directed) roughs up his hostage Connie (Dorothy Malone) to keep her from escaping, adding a bit of erotic kink to the storyline. Deciding to race her Jaguar across the border under a pseudonym, Frank locks the feisty Connie in a shed which she promptly sets ablaze. A friend of Connie’s happens to see the fire and rescues her, and Connie reports Frank to the police. Seemingly oblivious to the consequences, Frank recklessly plows through a roadblock at the border, tailed by Faber, a friend of Connie’s who crashes into a tree during the pursuit. Sabotaging his own chance for escape, Frank shows his true colors and sacrifices himself when he stops to rescue Faber. A breathless Connie roars up in a borrowed car just in time to witness this final plot twist. And wouldn’t you know it: those two crazy kids fall in love, and the film closes as the two embrace, with Frank agreeing to turn himself in and face trial.

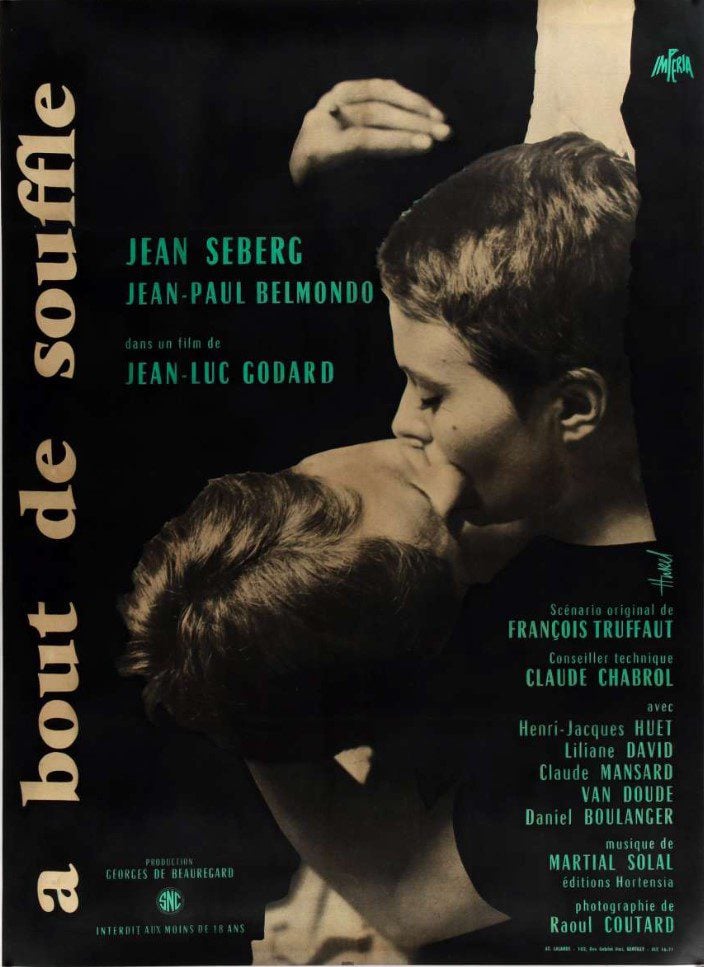

Although French director Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 debut film, “À Bout de Souffle,” carries a better pedigree in film circles, there are undeniable parallels between the two films. French filmgoers were more appreciative of Corman’s radical approach, including fast cars, faster jump-cuts (because neither director could afford tracking equipment), and a distinctly unwholesome leading man who was, as The New York Times described actor Jean–Paul Belmondo, “…hypnotically ugly.” Cars play a major role in “Out of Breath” (usually mistranslated as “Breathless”) as well as in “The Fast and the Furious,” with Godard casting Belmondo as Michel is a hapless car-thief, and electrifying the film with a breakneck race through Paris streets in a stolen convertible. The car-worship grounds both classics in the testosterone-laden cosmos of the 1960s antihero, a journey which begins with the Beach Boys in their hot rods and woodies (single-entendres so sophomoric they’re not even puns). Pop-psychologists now often describe cinematic cars as expressions of the phallic self, perhaps best epitomized by Spider-driving James Dean of the same era, and forever immortalized in 1967’s ode to youthful alienation, where Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock drives a new, red Alfa Spider in “The Graduate.” This in itself proves Corman’s prescience, and wry sense of irony, since his films initially seemed doomed to play the drive-in circuit.

Examining the films side by side, both Frank and Michel are seeming brethren in their narcissism, cool detachment, and disdain for authority. A noir-ish score by the Chet Baker Quartette infuses “The Fast and the Furious” with a pre-hip sense of lurking danger. American audiences being more sentimental than their French counterparts, “The Fast and the Furious” must close on corny note of redemption, while Godard’s work sneers at the thought of saccharine happy endings. Not surprisingly, Corman soon played an instrumental role in nurturing the talents of Hollywood’s bad boys circa the Summer of Love: Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda and Bruce Dern, along with shark-smiled Nicholson. Directors Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola also cite Corman as a mentor and perhaps unlikely source of inspiration. Corman played an essential cultural role of transforming the media figure of the outsider, whether Cagney-style gangster, intergalactic alien, or rubbery deep-sea monster, into the personification of the youthquake, the troubled, trouble-making, quintessentially misunderstood post-adolescent who drops out, and perhaps turns on and tunes in afterward, to paraphrase pop High Priest Timothy Leary.

Much of the reason for Corman’s early success was his pragmatic background in engineering (he graduated from Stanford University with a degree in Bachelor of Science in industrial engineering in 1947). While this academic credit honed his skill for squeezing a nickel until the buffalo cries, film was his secret passion. He took a messenger gig for Twentieth Century-Fox Studio shortly after graduating from Stanford, but pushed beyond the limitations of his menial duties to create his own opportunity by working unpaid on weekends. Although the offices were closed, production was full-tilt boogie on evenings, Saturdays, Sundays. This sense of enterprise and instinct for the long game allowed Corman to be present on set where the action was, setting down a clear path for his entrepreneurial future.

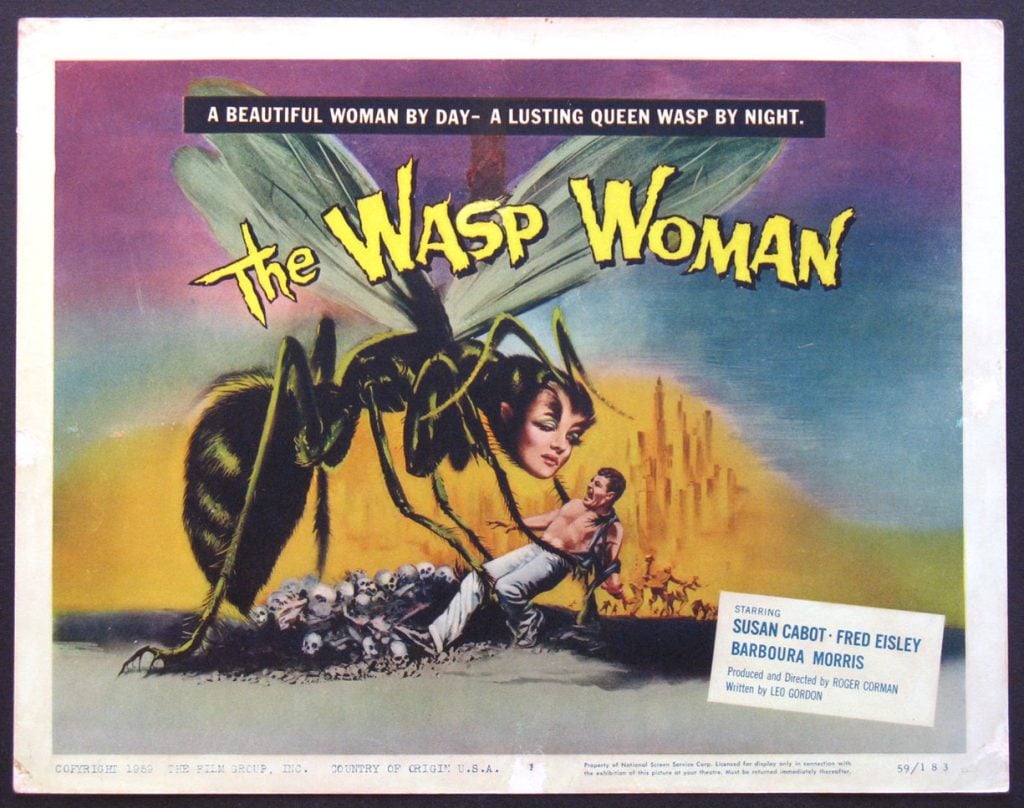

Corman established his niche early-on by working more efficiently than anyone else in Hollywood. He frequently shot two films simultaneously in order to make maximum use of sets and equipment, and often travelled to a location where a crew was already in place, again saving untold fortunes in time and money. Luckily, the scruffy corners of Los Angeles County could easily serve as almost anywhere, from wartime Korea to the Old West to mystical Biblical settings. And luckily early trash-terror Corman epics — “Swamp Women” (1956), “Attack of the Crab Monsters,” ”Teenage Doll,” and “The Undead” (all 1957), “The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent,” “She-Gods of the shark Reef,” “Teenage Caveman,”(all 1958), “A Bucket of Blood” and “The Wasp Woman” (both 1959) — just some of the gloriously kitschy titles Corman released before his 1960 breakout with “The Little Shop of Horrors”– hardly called for much in terms of nuanced setting or subtle ambiance.

More than two decades later, “The Fast and the Furious” is a lucrative action franchise that surely has surpassed even Roger Corman’s wildest dreams. A true international box office juggernaut, the franchise series features producer-star Vin Diesel as the underground street racer and notorious electronics thief who burns plenty of manly rubber eluding the LAPD. The current Marvel format-inspired iterations win increasingly broad audiences by integrating current pop culture icons including Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, rapper Lucacris, Gal Gadot (Krav Maga and Karate black belt martial artist, as well as former spokesmodel for Jaguar), and super-suave, Watts-born R+B singer Tyrese Gibson into the high-octane storylines.

The monster spin-offs now are made glossy, glitzy and glamorous with complex origin stories, astonishing CGI effects and massive, weapons-grade budgets that would have lasted the frugal Roger Corman a decade of filmmaking instead of a cinematic nanosecond. The franchise now is big box-office and solid family-fare. And Corman’s ragged, raw, original outlaw edge is long gone, along with the revving of engines and screech of “Thunder Road,” although the appeal persists. In Los Angeles, the boys of summer once again demonstrate their machismo with illegal street-takeovers, spinning their rides into donuts thrilling enough to make the nightly news, leaving behind occasional casualties and plenty of skid-marks. Vroom-vroom.

This review was written by Victoria Thomas (@Miss_Vickums), a Bronx-born pop culture writer who now lives in Los Angeles. She is the author of Hollywood’s Latin Lovers: Men Who Made the Screen Smolder (St. martin’s Press/Angel City Press) and contributes to several arts journals.