JACK NICHOLSON - THE ANATOMY OF A SUPERSTAR

Although Jack Nicholson has often described himself as a studio method actor, his screen alchemy defies mere technique. Directors, producers, co-stars and critics often compare his suave swagger to that of Cagney and Bogart, praising the leading-man charisma that has carried the actor through more than a half-century of film roles, many of them iconic, a few of them Oscar-winning. But they’ve got it all wrong. The enduring power of Jack Nicholson resides in the fact that Jack, at his absolute best, gives us the creeps.

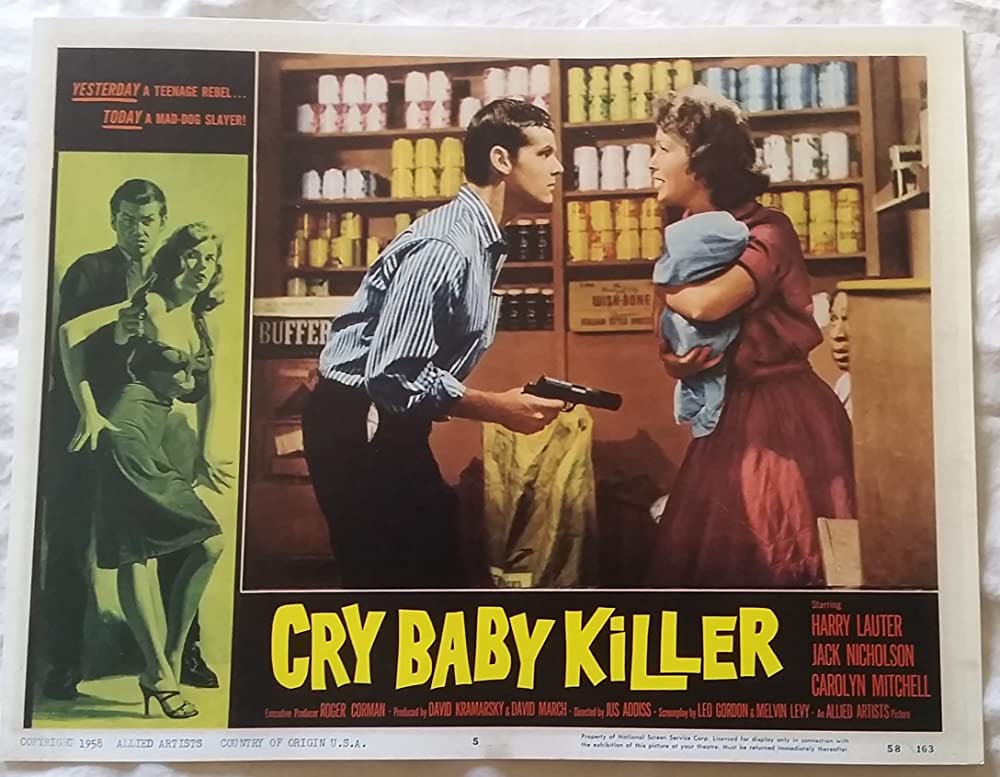

His first role was in 1958, as “The Cry Baby Killer,” a teen-scream thriller cranked out by uber-schlockmeister Roger Corman, with whom Nicholson would team for his first few roles. These early productions were aimed at young movie-goers who typically viewed them in drive-ins, where anticipated backseat action took precedence over anything on the screen. Awareness of this viewing modality allowed Corman and Nicholson to create campy cinema that gleefully crosses the line into self-parody. Nicholson carried these early lessons in excess with him into an exhaustive career of many big-budget hits, multiple memorable near-hits, and a few truly stinko duds. His portrayals are typically high-octane, with a level of stylized exaggeration that sometimes teeters on giddy caricature. And yet even at his most mirthful, there is an undertone of menace to Nicholson that keeps us watching, worrying, and wanting more..

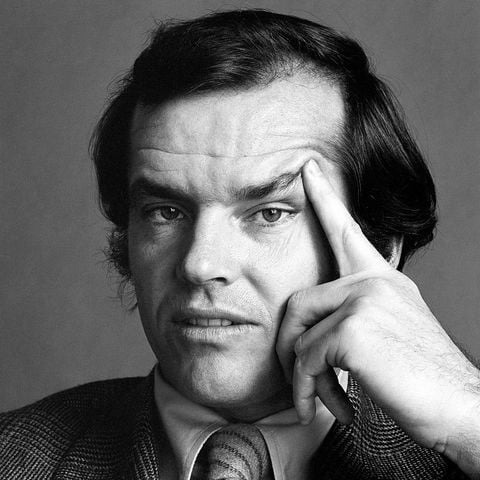

In the philosophy of looks theory, Nicholson displays what many consider to be an ideal facial structure: “hunter” eyes, meaning an eye shape that is narrow, and deeply set, exposing little or no upper eyelid, giving the eye a fierce, predatory look. By contrast, large, protruding eyes which expose a lot of the upper lid are widely perceived as “prey” eyes, resembling the wide, trusting eyes of a vulnerable cow or doe. Women with this doe-like eye structure are frequently perceived as receptive and therefore attractive.

Vulnerability is not a card in Nicholson’s dramatic deck. A pronounced browbone sets the stage for the actor’s masculine gaze in purely architectural terms. David A. Puts, PhD, Department of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University, speculates that in early human development, “…heavy brow ridges protect eyes from blows.” In addition to an eye-structure that’s small in size and deep-set, Nicholson’s eyes are also fairly close-set, meaning that they are no more than one eye’s width apart. This forward-facing placement further reinforces a predatory look, since carnivores evolved to focus on whatever is in their direct line of sight. By contrast, herbivores typically have eyes that are set far aparthypr- on opposite sides of the skull, to give the prey animal the best possible peripheral vision to detect approaching predators from all directions.

Adding still further to Nicholson’s naturally threatening bone structure is what cosmetic surgeons call positive canthal tilt (PCT). This refers to a slight uplift at the outer corners of the eyes. In esthetic terms, cosmetic surgeons recommend an upward tilt of no more than two degrees, and Nicholson’s facial geometry conforms to this equation. This subtle tilt makes his face look youthful, alert, canine, and a bit feral onscreen. Nicholson amplifies this upward motion with impressively arched eyebrows, signaling intense hyper-awareness, like a wolf closing in on the scent of a kill.

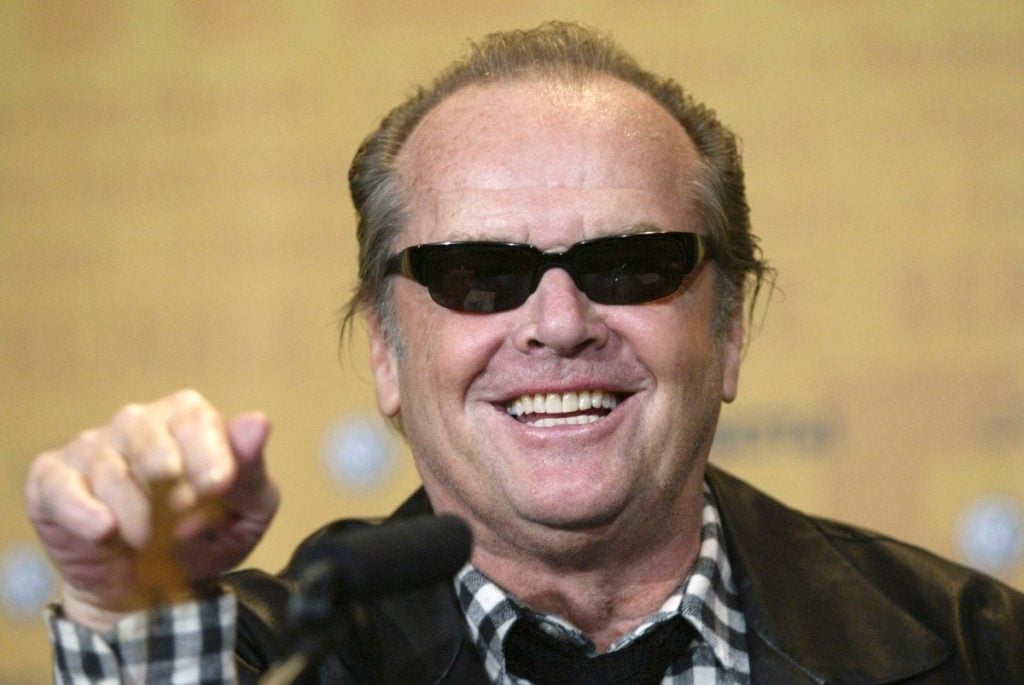

When Nicholson turns up the juice on a role, which is his wont, we witness the visual power of these features, especially the eyebrows. Much has been written about the actor’s “killer smile,” but his perfect dentition is simply a distraction from the damage soon to come. Remember that primatologists identify the baring of teeth as an act of submission. (When challenged for her somber expression in photos, Yoko Ono famously said “Smiles are for shopkeepers.”) In the case of Nicholson, his easy smile is a bluff; his eyes tell the real story. The gaze is steely in 1992’s “A Few Good Men” when he delivers the immortal line, “You can’t handle the truth.” In other more extreme roles, notably 1989’s Joker characterization in Tim Burton’s “Batman,” a more flamboyant Nicholson contorts his conventionally handsome face into a terrifying mask of depraved comedy. Nicholson had baited the trap many times before with his signature combination of conflicting sensations, hilarity and fear. Among the most notable examples: his iconic axe-wielding “H-e-e-e-e-e-re’s Johnny!” moment in Kubrick’s 1980 masterpiece, “The Shining,” a morsel of pure terror which Nicholson improvised.

And there were premonitions throughout the actor’s earlier performances. As Jonathan, the nihilistic lead in 1971’s “Carnal Knowledge,” Nicholson’s affect is flat, cynical, defeated. This makes his sudden morph into blistering fury, confronting Ann-Margret as his depressed wife, Bobbie, all the more electrifying. When she complains, “The reason I sleep all day is because I can’t stand my life!”, Jonathan responds, “You want a job? I got a job for you. Fix up this pigsty! You get a pretty goddam good salary for testing out this bed all day! You want an extra fifty dollars a week, try vacuuming! You want an extra hundred, make this goddam bed! Try opening some goddam windows! That’s why you can’t stand up in here, the goddam place smells like a coffin!” Nicholson ratchets up the intensity with each sentence until he’s breathless and red-faced, a foretaste of the eerie and truly sordid final scene where Louise, an elegant Manhattan call-girl played by Rita Moreno, strokes him out of his mid-life impotence with a chanted ode to his character’s narcissism. Moreno delivers her lines straight into the eye of the camera as though she’s coaxing a serial killer to spare her life.

Much earlier, in 1971’s “Five Easy Pieces,” Nicholson held audiences rapt in the role of another disillusioned loner, Bobby Dupea. The film’s most memorable moment is when the typically mild-mannered Dupea explodes in anger at a waitress at a truck stop diner when he tries to order something that’s not on the menu: toast. Compromising by ordering a chicken salad sandwich, he tells the server to “…hold the chicken salad…between your knees,” and ad lib line that brought the house down. As with his leering Ed McMahon impersonation in “The Shining,” Nicholson made it up on the spot and on the fly, summoning up his own private demons into play from the depths of who knows where.

In all fairness, Jack warned us. Consider the moment when Jack Nicholson first moved from the shadows of obscurity into the spotlight. The year is 1960, and Nicholson has been cast as a masochistic dental patient in Roger Corman’s (now) cult classic, the original “The Little Shop of Horrors.” As Wilbur Force, Nicholson is dissolving in psychotic giggles as he reads aloud from an issue of “PAIN” magazine in the dentist’s waiting room:

“The patient came to me with a large hole in his abdomen, caused by a fire poker used on him by his wife. He almost bled to death and gangrene had set in. I didn’t give him much of a chance. There were other complications. The man had cancer, tuberculosis, leprosy, and a touch of the grippe. I decided to operate.” Explaining to the dentist that he has three or four abscesses, a touch of pyorrhea, nine or ten cavities, and a lost pivot tooth, Wilbur Force cautions “Now, no novocaine. It dulls the senses.” When the dentist warns, “This is gonna hurt you more than it hurts me,” Force responds “Oh, goody, goody, here it comes! I’d almost rather go to the dentist than anywhere, wouldn’t you?” As a window into the subversive outlaw spirit of this micro-budget debut, the star, producer, and the rest of the filmmaking team jumped the fence of Charlie Chaplin’s old Hollywood studio where they shot “Shop” in two days, without permission from anybody.

In later roles, Nicholson often expanded his bag of tricks into the realm of the comedic grotesque. As the boisterous Randle McMurphy in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” Nicholson’s eye-rolling antics, including a faked lobotomy, earned him the Oscar for Best Actor in 1976. Director Miloš Forman was not amused, and Ken Kesey who authored the original novel was horrified. Occasionally in later roles, including “Prizzi’s Honor” (1985) and “Hoffa” (1992), Nicholson burlesqued his characters as bloated, two-dimensional buffoons, perhaps just to show audiences how low he could go, or perhaps in homage to his low-rent roots as a Roger Corman player.

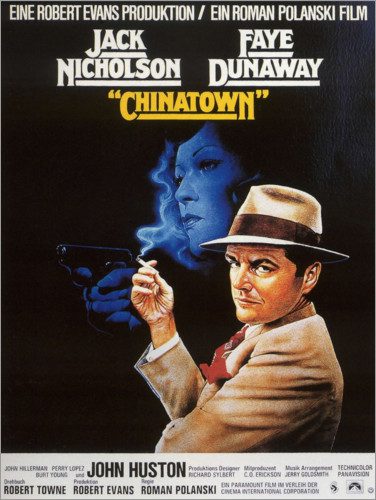

Nicholson’s Great White Shark-grin belies the tabloid darkness of his life in the glare of fame. Friends with Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate, Nicholson began sleeping with a hammer under his pillow while he skipped work almost daily to attend the Manson family trials in 1970. Four years later, Nicholson starred in the 1974 smash “Chinatown” directed by Polanski. Three years after that, Polanski was arrested at Nicholson’s home for the cocaine-enhanced rape of a 13-year-old model, Samantha Geimer. Anjelica Huston, daughter of the legendary director John Huston who starred alongside Nicholson in “Chinatown,” happened to stop by when Polanski and Geimer were behind closed doors. Huston and Nicholson had recently ended their long romance, and Anjelica dropped in unexpectedly to pick up a few of her belongings. She later told police that she observed nothing unusual, and that Polanski and the girl drove away without incident.

Nicholson has always loved a front-row seat to spectacle, whether courtside at a Lakers game, or up front beside Andy Williams during the 1977 trial of Williams’ ex-wife Claudine Longet, accused of killing her lover, alpine ski racer Vladimir Peter “Spider” Sabich in the shower. As with the Manson family trial, Nicholson barely missed a day in court. The titillating proximity of deceit, danger and death to innocence and beauty is the X-factor in the winning formula that elevated Nicholson from B-feature bit player to A-lister. The smile has never wavered, and the eyes are always scanning for the next conquest.

This review was written by Victoria Thomas (@Miss_Vickums), a Bronx-born pop culture writer who now lives in Los Angeles. She is the author of Hollywood’s Latin Lovers: Men Who Made the Screen Smolder (St. martin’s Press/Angel City Press) and contributes to several arts journals.