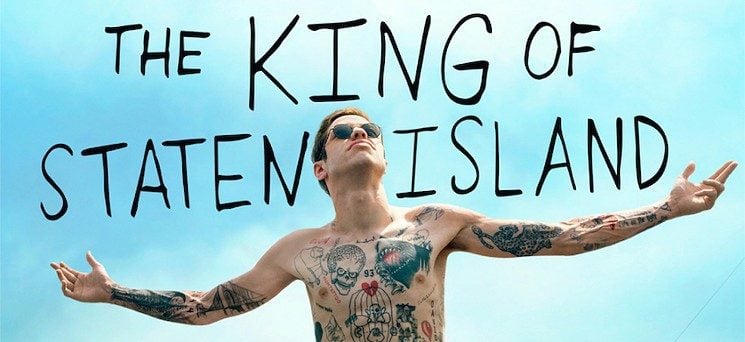

Judd Apatow’s latest film, The King of Staten Island, is another way of telling a boy’s tale of becoming a man at his own pace. Apatow, who is known for his in-depth character building, loves to write films where the main character is a male struggling to mature. This form of storytelling has helped pave the way for actors like Seth Rogan, who played a man child in the 2007 film Knocked Up, Jason Segal, who played the musician with no career drive in the 2008 movie Forgetting Sarah Marshall and in Apatow’s directorial debut The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Steve Carell plays a middle-aged man who has never been in a serious relationship. These characters’ growth in these films leaves the audience with a sense of “everything will be alright.” Unfortunately, the King of Staten Island, which stars Pete Davidson, does not have this same effect.

The film opens with Davidson’s character, Scott Carlin, attempting suicide while driving a car down the highway. Scott closes his eyes and speeds up only to burst his eyes open at the last moment to see he is about to slam into the rear end of a stopped car. Now, regretting his suicidal thoughts, Scott swerves around the stalled vehicles and, as he pulls back into his lane, buckles his seat belt and repeats the words “I’m sorry” multiple times.

Opening a film with this type of scene is a way of showcasing the main character is dealing with some serious emotional issues that could be dealt with as the film progresses. However, what we find is that Scott repeats throughout the film that he is “screwed up” but never attempts to confront these issues or seek any help for them. This character’s devolvement leaves much to be desired that throughout the film. Although Scott does grow in some ways and attempts to change his ways to make those he cares about happy, it feels flat and lackluster, missing the audience’s mark on emotional connection. The scene with Scotts Friend Kelsey (Bel Powley) at the end of the movie attempts to showcase how Davidson’s character has grown and wants to be there for his friend. However, what plays out seems to be a phony attempt to convey deeper feelings for someone than Scott has. The film’s writing is not to blame in this situation but rather Davidson’s ability to show depth in his acting. As the star of the film, Pete Davidson does a great job delivering the whiny stoner lay-about. Still, when it comes to his cast members’ emotional connection, the ball is metaphorically dropped. In one scene, Scott lets Kelsey know he is messed up and cannot care for others the way “normal” people do. Here again, it should have been a critical moment in the film where viewers get a glimpse into why Scott is the way he is and the reasons behind his emotional disconnect. Scott’s father was a firefighter who died, saving lives like Davidson’s real father (Scott Davidson) on 9/11. The connection between the character Scott Carlin and the actor Pete Davidson had the opportunity to let some genuine emotions come out on screen. These emotions never came through in the end, and due to this, the entire movie stays around the surface and never dives deep as one would hope.

However, the characters and actors surrounding this main story are full of emotion and connect well. A running theme throughout the 2 hours and 16 minutes of screen time are that Scott wants to be a tattoo artist. Using his friends as practice dummies, Scott shows a lack of care or consideration for those around him. While at the beach, a ten-year-old stumbles into Scott’s group of friends and asks for a tattoo. Although the one friend with common sense in this situation, Igor (Moises Arias), protests, Scott tattoos the child anyway. After feeling the needle’s sting, the kid runs away screaming, which results in his father, firefighter Ray Bishop (Bill Burr), later confronting Scott at home where he lives with his mother Margie (Marisa Tomei). Ray and Margie spark a connection at this moment, and Ray later returns to apologize for his actions and asks Margie on a date. The back and forth from Burr and Tomei in the few scenes they share steals the entire film. Scott cannot come to terms with his mother dating another firefighter and feels like his Ray is a cheap knock-off version of his father. When Scott turns on Ray and attempts to break up the relationship, he has with his mother, and a cloud is placed over Ray for the remainder of the film in an unfair way. While the things said about Ray’s issues with gambling could be true, most of what was said came from his ex-wife, and the film never gives more detail.

The main flaw this film has is the lack of closure each character gets. In an attempt to rob a drug store, Scott’s friends all end up either shot or arrested, and their storyline ends there. Teased a bit that Margie and Ray get back together, their relationship’s solidity is still in question at the film’s closing. Scott’s character, more than anyone’s, is left with many unanswered questions. The film leads up to the central moment of Scott becoming a man and growing up. However, the film ends with him still struggling to complete that growth. Every attempt in the movie to achieve this happened without Scott’s consent. He has been kicked out of his mother’s house, not getting the tattoo apprenticeship he wanted and deciding on whether or not he wants to be a firefighter like his father and Ray. Led to believe that Scott will walk in his father’s footsteps, the closure does not play out on the screen.

In the end, there is much left desired with this film, and although there are some great moments and excellent acting, the main focus of the movie drops the ball multiple times and ends in a weird place of uncertainty.

Written exclusively for TheLastPicture.Show by Jacob Ruble

Disclosure: The links on this page are “Affiliate Links” and while these are shown at no costs to our viewers, they generate commissions for our website(s)