If you’ve recently visited your doctor, chances are he discussed a new term you’ve never heard of: body mass index , or BMI . But, what is BMI? And, how does it affect your health?

A Primer on Obesity

Muffin top. Love handles. Beer belly. Call it what you want. Most of us are familiar with the struggle of managing our weight. A 2007 survey published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that 63% of American men and women are overweight or obese. Weight loss has become a $20 billion industry, responsible for the South Beach Diet, Weight Watchers, the Atkins Diet, Nutrisystem and more.

According to the American Heart Association, heart disease claims more than 610,000 deaths a year – that’s one-fourth of all annual deaths. While there’s nothing you can do about risk factors like advancing age and gender, other factors like living a sedentary lifestyle and obesity can be successfully managed and reduce your risk for heart disease.

As you gain weight, you put more stress on your heart in an effort to pump blood around to an ever-increasing body size, leading to hypertension . Weight gain is often associated with higher triglycerides , higher LDL cholesterol (the bad kind) and lower HDL cholesterol (the good kind). Next, comes arthritis, joint pain, and the threat of stroke and diabetes. Eventually, you realize it’s time to make a change.

How Fat are You?

Total body weight consists of fat and fat-free tissues, or everything that isn’t fat. The normal percentage of fat tissue for males is 10-15% of their total body weight; 15-25% for females.

In scientific circles, it’s been said that the only true way to measure how much fat you’re storing is to boil your body down and skim the fat off the top. For most people, that’s not a plausible option. So, science and medical communities have developed a number of ways to estimate how much fat and fat-free tissue you have using laboratory techniques. The most popular methods include:

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)

- underwater weighing

- whole body plethysmography (Bod Pod)

- skinfold measurements

- bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA)

- waist to hip ratio measurements (WHR)

While none of these are absolutely accurate, they do provide reasonably valid estimates. The problem is they’re often prohibitively expensive, require technical expertise and are difficult to perform in a doctor’s office. An easier, more representative method was needed. Enter the concept of body mass index, or BMI.

The Body Mass Index

Calculating body mass index has been around for years, but only recently used in clinical settings. The first calculations were developed in 1832 by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician and astronomer. He called them the Quetelet Index . In 1972, the Quetelet Index was renamed to body mass index by Ancel Keys, an American physiologist who was one of the first people to associate diets high in saturated fat with heart disease.

Body mass indices are calculated using either simple formulas or charts:

Metric formula for calculating body mass index :

BMI = Weight (kg) / Height (m) 2

Imperial formula for calculating body mass index :

BMI = (Weight (lbs.) * 703) / Height (inches) 2

For example, a 6 foot male weighing 180 lbs. has a BMI of 24.4

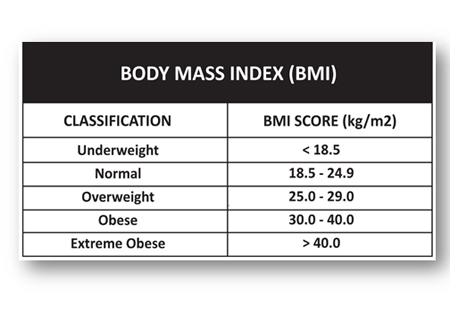

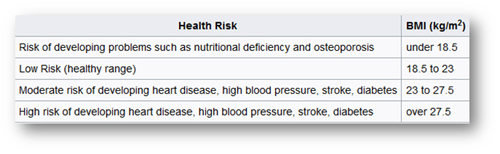

Referring to the chart below, a 24.4 body mass index is at the upper end of the normal classification.

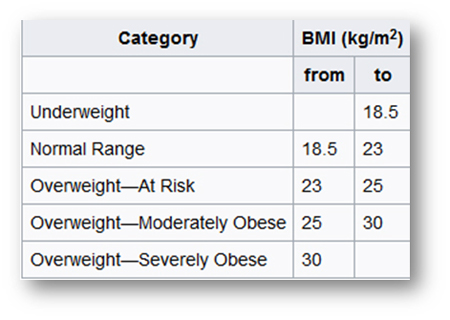

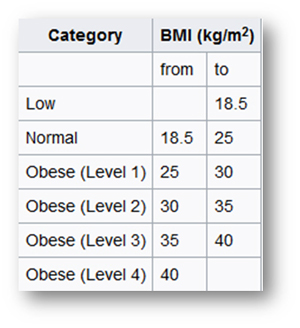

Body mass indices can also vary by geographical region. The following charts represent BMIs for Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore:

Hong Kong

Japan

Singapore

If you’re not comfortable with mathematical equations, you can use one of the handy BMI calculators available on the Internet:

Source: Mayo Clinic

Interpreting Body Mass Index – It’s Successes and Limitations

Calculating BMI with “one-size-fits-all” formulas has as many disadvantages as advantages. The same formula is often used on all sexes, ages, activity levels, ethnicity, and lifestyles – rail-thin teen-agers and clinically obese Sumo wrestlers. When Ancel Keys first published his findings, he was quick to point out that his formulas were appropriate for population studies and inappropriate for individual evaluations . Nevertheless, due to its simplicity, BMI calculation continues to be a quick, affordable tool for reflecting normal weight and percent body fat.

Studies have shown that using BMI calculations adds approximately 10% body fat for people with large and tall frames. It deducts 10% for shorter, thinner people. Using the current BMI calculations suggests that smaller adults carry higher levels of body fat, even though they may have normal BMIs. Conversely, taller, larger adults may be healthy, with lower percentages of body fat, even though they have high BMIs.

BMI calculations often overestimate percent body fat in individuals with high levels of fat-free tissue. For example, a 350 lb. NFL offensive lineman would score extremely obese. More sensitive measurement techniques like DEXA, underwater weighing and even skin fold measurements more accurately differentiate between professional athletes and normal adults.

In 1998 the National Institute of Health and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention re-aligned their findings with those of the World Health Organization . The results lowered the upper level of normal from 27.8 to 24, redefining 29 million adults from healthy to overweight .

Four years earlier, the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES) published their findings: 59.8% of men and 51.2% of women had BMIs of over 25 (overweight). Two percent of men and 4% of women had BMIs over 40 (extremely obese).

Finally, a 2005 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that overweight subjects had death rates the same as subjects of normal weight. Subjects on the periphery, underweight and obese, had higher than normal death rates.

Children and Special Populations

Do adult BMI formulas work equally as well for children and special populations? Apparently not. Recently, new charts and calculations have appeared, specifically for them. One critical difference is gender. Unlike their adult counterparts, BMI calculations for children include an additional male/ female variable to take into account the different rates that children of different genders grow and mature. Some populations, like Singaporeans, store a higher proportion of body fat than their Caucasian counterparts – even with the same BMI – so BMIs for some ethnicities may be questionable. Studies on other countries will undoubtedly follow.

Conclusions

Given all of the drawbacks with using BMI formulas, should we still depend on them? Yes and no.

An important, well-established consideration is where people store fat. Apple-shaped ( android ) people who store excess fat around their waist, are at a higher risk for heart disease than pear-shaped ( gynoid ) people who store excess fat around their hips, thighs and bottom. BMI calculations are oblivious to how either type stores fat.

Keeping in mind that the current formulas were designed to be used in evaluating large populations , it’s still an affordable, simple to use, and reasonably accurate way to identify obese individuals in clinical settings. At the same time, clinicians who continue to use BMIs in the office may be providing their patients with inaccurate information – information that could have significant health ramifications. Until more accurate, inexpensive tools are available, using BMIs may be the best solution.

Source: Forbeautyandcare.com