Very few writers really know what they are doing until they’ve done it.

– Anne Lamott

This quote from Anne Lamott resonates with me quite a bit. I seldom know what I’m doing until I’ve done it. I also seldom know what other writers are doing either. I recognize what I enjoy reading … aaaaand I’ve little idea why I enjoy it.

That’s what makes the topic of linguistics and language so fascinating to me because it helps explain all the whys behind the writing I love, the tweets I read, the updates I favorite, and the copy I crave.

There’s an art and a science to writing that sits just below the surface, and I’d love to share with you what I’ve learned about how to reveal it and incorporate it into your marketing messages—and how to write copy that people love!

Linguistics, Microstyle, and the Beauty of Small Writing

Simplicity is not a given. It is an achievement, a human invention, a discovery, a beloved belief.

– William H. Gass, Finding a Form

When I look at a format like Twitter, for instance, I see a 140-character limit that has helped explode our use of writing and creative expression. We oftenthrive creatively when given constraints, and I think this has absolutely been true on social media where the messages are short and simple, yet the effect resonates just as much or more.

What writers and sharers have found effective (purposefully or accidentally) is the power of a few particular types of word science. I’d love to get into each of these in fine detail in this article.

What is linguistics?

What are literary devices?

What is microstyle?

What is syntax?

And if it helps to have a little nudge of encouragement while you’re discovering the best way to write, here’s some advice I hold dear from William Zinsser:

Writing is hard work. A clear sentence is no accident. Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair.

I’ve often found that the hares who write for the paper are overtaken by the tortoises who move studiously toward the goal of mastering the craft. …Forget the competition and go at your own pace. Your only contest is with yourself.

Sometimes (okay, a lot of times) I find myself clicking on an update or a tweet because of a single word. The word might be a power word, one of those catchy words that convert and get people to click. Or, and this is where I’m keen to learn much more, the word just sounds cool.

Now, how do you find a cool-sounding word?

One helpful bit of context is to think of these words within the bigger idea of syntax: way that words are pieced together into phrases, clauses, and sentences. Within syntax, the specific choice of word—its rhythm, its sounds, its letters even—can make the difference between a sentence or phrase that flourishes and one that flops.

Here’s a bit more about the pieces and parts of these perfect (and cool!) words.

Stop Consonants and Glide Consonants

Stop consonants are those that cause the vocal tract to block when pronouncing the consonant. Glide consonants do not obstruct the vocal tract and are quite frictionless when spoken.

Huh?

That was my first reaction, too! A few examples might help. Sound each of these out, either in your head or out loud, and notice the way each of them feel as you’re saying them.

Somewhere a ponderous tower clock slowly dropped a dozen strokes into the gloom.

– James Thurber, The Wonderful O

Time flies over us, but leaves its shadow behind.

– Nathaniel Hawthorne

In these examples, the first uses a handful of stop consonants, giving the sentence a staccato vibe and a certain, ticking rhythm. The second example uses glide consonants, allowing the words to flow from one to the next.

The effect of a stop consonant is to slow the flow of a word or sentence, thereby bringing a certain rhythm or symbolism to what you’re saying (or reading). Often these stop words help highlight what comes next or build to a grand conclusion—a bit like a countdown when used in succession.

Stop consonants include:

- t

- d

- k

- g

- b

- p

Glide consonants, on the other hand, can lead to a really smooth flow from word to word and in the greater context of a sentence or paragraph.

Glide consonants may include:

- l

- r

- j

- w

Examples:

Stop consonants:

Glide consonants:

Let’s get into the rhythm of the word itself. Rhythm comes from syllables, the individual units of words that make up the whole. For instance, water has two syllables (wa-ter), and inferno has three (in-fer-no).

Now for the science-y good stuff. There are some really neat distinctions to be made with the order and emphasis of syllables. At the simplest level, these come down to iambs and trochees.

- Iambs – an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one (dee DUM)

- Trochees – a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one (DUM dee)

The difference, as Christopher Johnson notes in Microstyle, can be quite striking:

Iambs tend to sound lighter and softer, and trochees tend to sound heavier and harder.

“Feminine” brand names, like Chanel, are often iambs; “masculine” ones, like Black & Decker, tend to be trochees.

Most people “feel” this difference even if they find it hard to pinpoint.

(If you ever find yourself naming a company or a product, this seems like super helpful advice!)

What effect do you want to make with your social media update? Are you going for lighter and softer or heavier and harder? Which one suits your brand’s voice and tone best?

For instance, I’m writing up a bunch of customer stories currently. Do I want to call them case studies (DUM dee) or user reviews (dee DUM)?

Examples:

Iambs and trochees might seem a bit foreign to the social media space, but they’re commonplace for poetry. Heard of iambic pentameter? It’s basically the placement of five consecutive iambs in a line of verse, like this from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night:

If music be the food of love, play on.

So here’s where things get really interesting for the catchy social media updates you might spot.

Can you make a social media update sound like poetry?

Sure enough! We just touched on iambic pentameter (five iambs in a row), and there’s tons more. A couple of my favorites that I’ve found are anapaests and dactyls, which deal with the distinction between three-syllable words and phrases—basically a bit more wiggle room when composing longer updates or looking for longer words.

- Anapaests – two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed one (dee dee DUM)

- Dactyls – a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed ones (DUM dee dee)

And like iambic pentameter, these anapaests and dactyls can fit within meters, too. Here’s an example of an anapestic tetrameter, which is when four consecutive anapaests appear.

And today the Great Yertle, that marvelous he

Is King of the Mud. That is all he can see.– Dr. Seuss, Yertle the Turtle

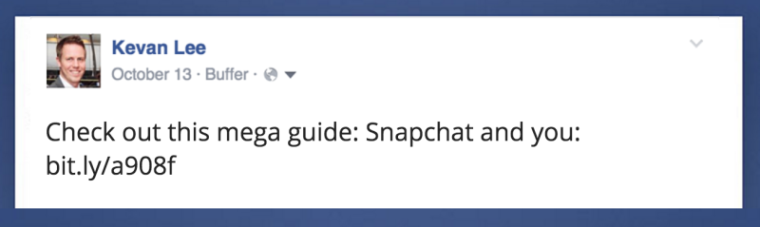

OK, so not if we were to spin this into the social media updates that we all write, would the advice to be “take a poetry class”? Not really. Where these syllables and arrangements can be most effective is in the noticing of rhythm when you’re writing an update. Does something sound oh-so-close to rolling off the tongue but is just slightly stuck? Maybe it’s just a syllable away from an anapestic tetrameter.

Examples:

Check out this mega guide: Snapchat and You

Create a New Word

In need of a great word? Why not make one up?

Christopher Johnson’s book Microstyle lists seven ways to create a word from scratch. Many of these borrow from age-old literary devices like Portmanteau, which is the joining together two or more words in order to create an entirely new word. Here’s the full list (along with some examples of each).

- Reuse an existing word (Apple, spam)

- Create a new compound word by sticking two words together (YouTube, Facebook)

- Create a blend by combining one part of a word with another word or word part (Technorati, pastarazzi)

- Attach a prefix or a suffix to a word (uncola, Bufferoo)

- Make something up out of arbitrary syllables (Tivo, Cee-Lo)

- Make an analogy or play on words (podcast, Sketchpaper)

- Create an acronym (SCUBA, guba)

A bonus literary device: Spoonerism: interchanging the first letters of some words in order to create new words. This is mostly done in error or, if intentionally, done as a joke. Still, I’d expect it to be catchy if it were to pop up in a timeline!

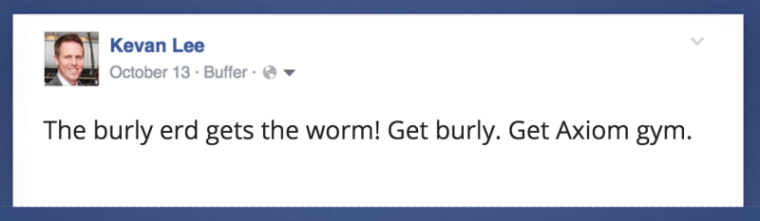

Example:

(Yikes, that might be a terrible one. I’m new to this!)

Alliteration

Here’s one you may recognize. Alliteration is words beginning with the same letters or letter sounds.

- A dozen delicious donuts

- Throwback Thursday

- Facebook on a flip phone? Fantastic!

You’ll see alliteration used in headlines quite often, particularly coupling a listicle number with a following adjective like 7 Sensational Whats-its or 10 Terrific Who’zles. There’s even a small bit of thought that prime numbers work so well in listicles because they can be easily paired with lots of alliterative adjectives and nouns.

Bonus tip: A cool way to use alliteration is to string together a ton and then break off the pattern suddenly. (The word you use to break things off will stand out quite starkly, in a good way!)

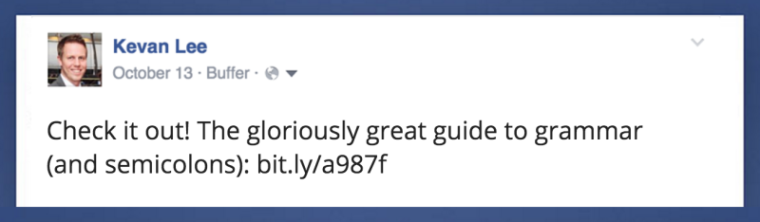

Example:

Anagrams

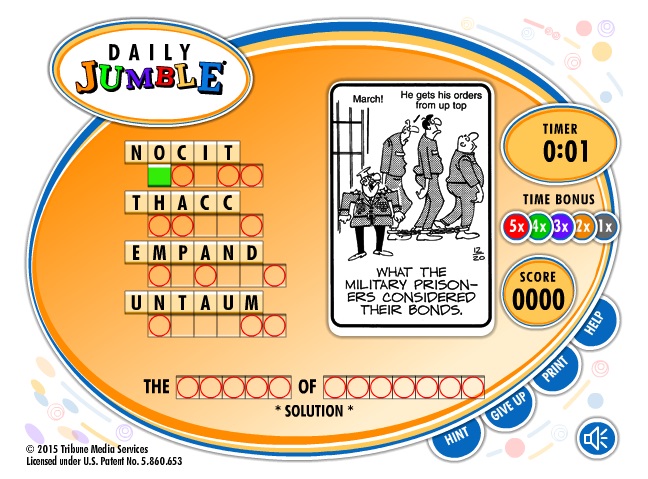

Have you ever seen this puzzle in your newspaper?

It’s built on anagrams, the jumbling of word parts to make a new word.

In the example above, the jumbling makes nonsense words, which are great for puzzles. Where the real value in anagrams lies for your social sharing is with the creation of other words, using the same letters in the original. There’s a neat tool out there from Wordsmith.org called the Internet Anagram Server. Here’re some examples I grabbed:

Kevan Lee = Navel Eek

San Francisco = Casino Francs

Product Hunt = Doc Truth Pun

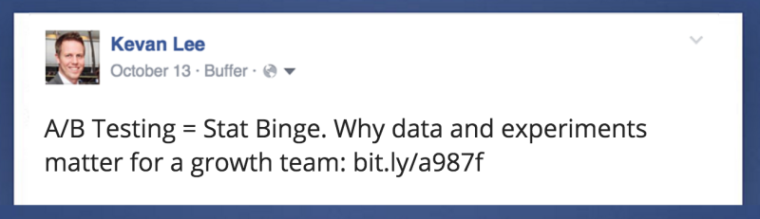

Example:

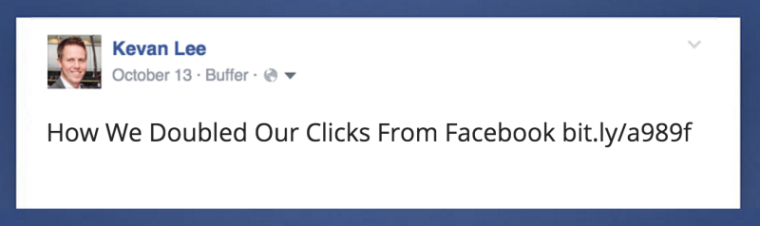

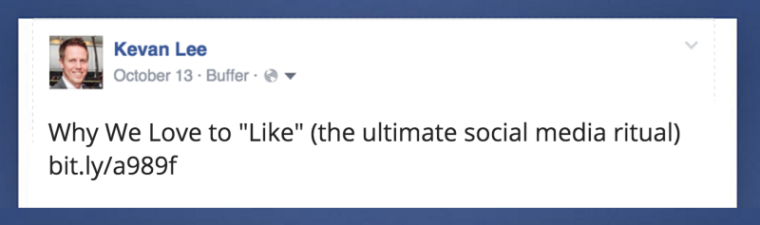

Marketing copy is built on great sentences. Facebook updates, tweets, Pinterest captions, blog post intros—these are all incredible places to string together a subject/verb in a way that catches attention and gets more clicks.

And here’s the really awesome thing: Tthe best sentences likely already come intuitively for you!

The tips below, which include some neat linguistic approaches and literary terms, are those you’d recognize in your favorite sentences and in the catchy sentences you’re already writing. Hopefully, knowing the science behind what makes these great can help take your sentence writing to the next level.

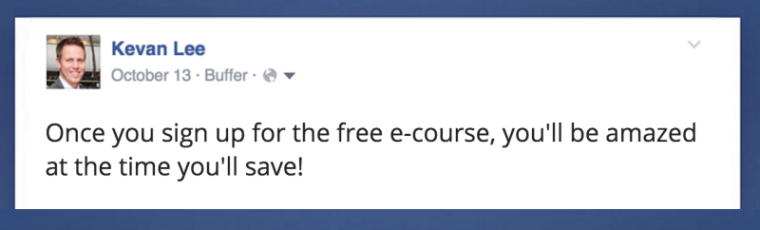

End Your Sentence With Strong Words

This is a lovely, simple tip: When composing your sentence, be sure to place a strong word or two last.

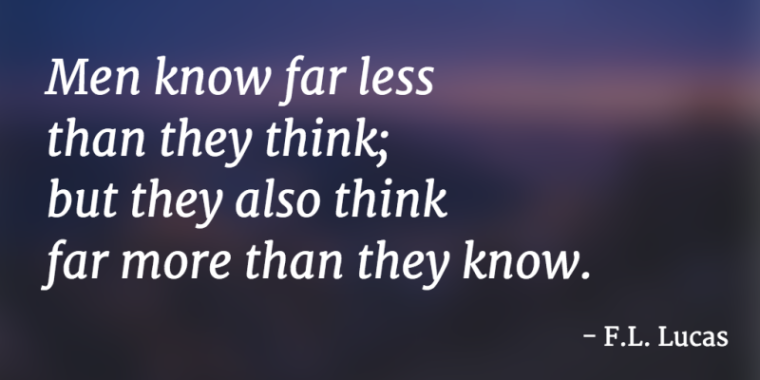

F.L. Lucas in his book Style: The Art of Writing Well (one of my all-time favorite writing books, by the way) explains it here—and in so doing, gives a great example:

I suggest that anyone who goes through the next thing he writes,seeing to it that most of his sentences end with words that really matter, may be surprised to find how the style gains, like a soggy biscuit dried in the oven.

Examples:

We’re so thrilled to announce the latest version of the Buffer app today: Automated Monitoring w/ in-Home Churro Delivery. Get the full details over on our blog post, including your first free churro.

As opposed to:

New Automated Monitoring (w/ churros!) is now live within the Bufferdashboard. Take it for a spin, get a churro for free, and tell us what youthink!

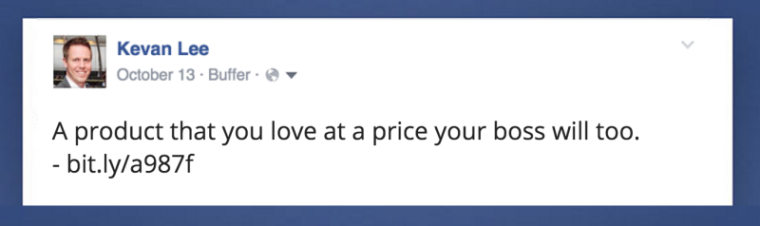

Use Climax Expression

The key to a climax expression is simply this: Whatever your most important phrase is within your sentence, have it come last.

The phrasing and order can really make a big difference. Take this example from Dwight Bolinger in Aspects of Language:

After he ate, he left the house answers the question, “What did he do after he ate?”; He left the house after he ate answers the question “When did he leave the house?” The climax expression comes last.

Linguists have found that many languages do the opposite: something called sentence perspective, where the known elements (e.g., “After he ate”) come first and the unexpected elements (what happened after he ate?) come last.

English takes a different tack, moving the strongest phrase last, regardless of whether it’s known or unknown.

It’s a small, really subtle difference, with the takeaway being: Put your strongest phrase last, as often as you can (and don’t mind breaking any rules).

It not only can change the complexion of the sentence, but it also tells the reader which part to focus on the most.

Examples:

As opposed to:

If you’re interested in saving more time, sign up for our free e-course.

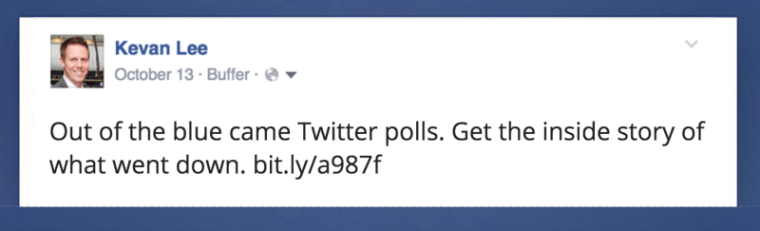

Inversions

A typical sentence construction might be: Subject > Verb > Adverb.

With an inversion, this order gets flipped entirely around: Adverb > Verb > Subject.

Talk about noticeable!

It might seem a bit odd to do at first, though the effect is quite catchy and elegant.

Examples:

Into this grey lake plopped the thought, I know that man, don’t I?

– Doris Lessing, Children of Violence

Parallelism & the Art of Repeating Things

With parallelism, you repeat words and sentence structures in a strategic way, building to a cohesive sentence or two that compounds on itself the more similarities it shares.

Within the DNA of parallelism is rhythm, which tends to be a common theme in a lot of the strategies mentioned here. And you’ll probably start to recognize parallelism in some of the catchiest quotes and passages from speeches and literature, too. Here’s a teaser:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted…

– Ecclesiastes: 3:1-2

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days nor in the life of this administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

– John F. Kennedy, inaugural address, January 20, 1961

Elliptical Construction

An ellipsis (or ellipticatl construction) is a linguistics technique that occurswhen writing a series of similar phrases and removing the similar parts that may be understood by the reader. (The sentence still sounds good, by the way; all the most important sentence parts are still there.)

There are a handful of really neat advantages to this style:

- Gives the reader a voice by allowing him/her to fill in the missing pieces

- Provides surprise with missing words

- Emphasizes the missing words (since the reader must figure them out herself)

- Removing words can create a sense of energy and brevity

Examples:

My Juvenal and Dante are as faithful as I am able or dare or can bear to be.

– Robert Lowell, Near the Ocean

No, I have never seen this face which you show me in the photograph. You would hardly forget it, would you, sir, for I’ve seldom seen an uglier.

– Conan Doyle, The Six Napoleons

It often happens that the sicker man is the nurse to the sounder.

– Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

Metaphor Versus Simile

There’s this great description of the difference between these two, from Christopher Johnson’s book Microstyle:

A metaphor is when you say one thing is another thing, and a simile is when you say one thing is like another thing.

A simile uses the words “like” or “as” to draw the comparison.

A metaphor implies a bit more indirectly.

In both cases, you’re using a known object to help describe a lesser-known one, which can be great for helping to explain new concepts quickly and easily on social media.

Example:

Incremental Repetition

This device is used when writers add to something that has been repeated, lending the repeated word or phrase more emphasis.

Examples:

He was a simple man, a simple man with a dream.

She was lovely, lovely beyond words.

There is much to be gained, to be gained from losing.

Just for Fun: Swifties

These phrases are clever parodies that occur when quoting someone and attributing the quote using a pun.

“You got a nice butt, lady,” he said cheekily.

“I’m the plumber,” he said, with a flush.

The phrase originated with a series of Tom Swift books (similar to Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew) where the author was fond of finding fresh ways to say “said” when quoting a character. The key example:

“We must hurry,” said Tom swiftly.

A swifty was originally known as a Tom Swifty, thanks to this example.

Example:

Paragraphs are almost as important for how they look as for what they say; they are maps of intent.

– Stephen King

Do you have a favorite paragraph?

It’s kind of an odd thing to favorite, or to notice really. Yet paragraphs are so important in building the structure of blog posts, e-books, even a long social media update.

There’re so many different ways and styles of writing and organizing paragraphs. Copywriters often go with single sentences as paragraphs. Others bundle them together in threes and fours. Yet no matter how the paragraph comes together, these tips on paragraph writing can work to take a paragraph from good to great.

Use Short, Be-Sentences to Start a Paragraph

We all know what a short sentence looks like. (I’m familiar, though I could definitely use them more!)

But a be-sentence? That was a new one to me!

Be-sentences are those that include a be verb. And what are be verbs? Here’s a list:

- am

- is

- are

- was

- were

- be

- being

- been

In Virginia Tufte’s Artful Sentences, she writes about how short sentences serve to introduce the paragraph, helping the reader move easily into a new topic. The be-sentence works singly or in pairs or triplets.

Examples:

In the morning it was all over. The fiesta was finished. I woke about nine o-clock, had a bath, dressed, and went downstairs. The square was empty and there were no people on the streets. A few children were picking up rocket-sticks in the square …

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Use Literary Devices

Running through the list of literary devices (there’s a complete list over at Literary-Devices.com), I was amazed at a) how many there are, b) how many I had heard of before, and c) how many I had forgotten about!

Here’s a short list of the ones that might be most helpful for adding some sizzle to your social media sharing. They’d make for great paragraphs!

Allegory – conveying an abstract concept by using a concrete object as an example

Analogy – conveying a new idea by referencing a familiar one

Anastrophe – swapping the placement of the noun and adjective

Anthropomorphism – giving human qualities to a non-human object

Assonance – repeating of vowel sounds within a sentence or phrase

Consonance – repeating of consonant sounds within a sentence or phrase

Euphony – the use of phrases or words that are known for producing melody or loveliness in the sound they create

It has been said that the phrase “cellar door” is reportedly the most pleasant-sounding phrase in the English language. The phrase is said to depict the highest degree of euphony, and is said to be especially notable when spoken in the British accent.

Internal Rhyme – forming a rhyme in only one line of verse

“We were the first that ever burst.”

– Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Kennings – related to works in Old English poetry where the author would use a twist of words, figure of speech or magic poetic phrase or a newly created compound sentence or phrase

- Battle-sweat = blood

- Sky-candle = sun

- Whale-road = ocean

- Light-of-battle = sword

Hand-computer = iPhone

Malapropism – misusing words by substituting words that sound similar but may have very different meaning

Metaphor – implying one subject to be another, helping to better understand a lesser-known subject by relating it to a more well-known one

Onomatopoeia – words that sounds like the sound they depict

Oxymoron – when words that seem to be contradictory appear next to each other (e.g. Jumbo Shrimp)

Puns – a joke, playing on the different meanings of same or similar-sounding words or phrases

The Way Shakespeare Would Have Facebooked

Wouldn’t Shakespeare have been a rad Facebook user? His sonnets and plays are chock full of amazingly well-constructed sentences and thoughts that would be so fun to see in short bursts on social media.

Here’s what he and his contemporaries had at their disposal: Rhetoric and syntax, those bits of language that we all know and love (and notice), but can less often name.

Rhetoric is the use of language to affect an audience; and syntax is the unique way that we form phrases, clauses, and sentences.

Rhetoric and syntax are close cousins to literary devices; in fact, literary devices often help make up the snappy rhetoric and syntax that is much-loved in writing and speech. I touched on some of the well-known devices above. There’s a ton of old-school ones, too, that Shakespeare and friends got great use of.

Here’s a big list of a huge number of rhetorical devices that could work wonders in your social media updates. (A lot of the obscure ones here came from a book called Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric — it’s a wonderful read, and so too is Demian Farnwoth’s recap here).

Here’s the full list of 22:

1. Epimone – Repeating a phrase

2. Epizeuxis – Repeating a word

3. Epanalepsis – Repeating the same word or phrase at the beginning and end of a sentence

4. Anaphora -Repeating the same word or phrase at the start of consecutive sentences or clauses

5. Epistrophe – Repeating the same word or phrase at the end of a series of sentences or clauses

6. Symploce – Repeating words at the start of successive sentences or clauses and at the end of them, often with just a small change in the middle.

7. Anadiplosis – Using the same language at the end of one sentence or clause and at the start of the next – an ABBC pattern.

8. Polyptoton – Repeating the root of a word with a different ending.

In so far as religion is gone, reason is going.

– G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

9. Isocolon – Using successive sentences, clauses, or phrases similar in length and parallel in structure.

The louder he talked of his honor, the faster we counted our spoons.

– Emerson, Worship (1860)

10. Antithesis – Juxtaposing parallel but contrasting ideas or images.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity,

– Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

11. Oscillation – Begins a passage with parallel elements of one length, then shortens them, then ends with a long phrase.

12. Chiasmus – Repeating words or other elements with their order reversed.

He does not possess wealth; it possesses him.

– Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

13. Anastrophe – Making words appear in unexpected order.

The association of interest between Britain and France remains. The cause remains. Duty inescapable remains.

– Churchill, London radio broadcast (1940) 2678

14. Polysyndeton – The repeated use of conjunctions.

15. Asyndeton – Leaving out a conjunction where it might have been expected.

16. Præteritio – When the speaker describes what he will not say, and so says it, or at least a bit of it, after all.

The proceedings opened with a speech from my colleague, of which I will say nothing. It was deplorable.

– G.K. Chesterton, Manalive

17. Aposiopesis – Breaking off a sentence and leaving it unfinished.

18. Metanoia – Correcting oneself.

19. Litotes – A speaker avoids making an affirmative claim directly and instead denies its opposite.

20. Erotema – Asking a question that does not call for a reply.

21. Hypophora – The speaker asks a question and answers it.

22. Prolepsis – The speaker anticipates an objection (not necessarily a question) and comments on it.

And here’s a bit more on the first six—all of which could work great on social media.

Repeating a Phrase

Official term: Epimone (“eh-PI-moan”)

Using multiple phrases is something you might be quite familiar with—lots of exclamations use it, lots of titles and subjects, too.

Examples:

The horror! The horror!

– Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

Repeating a Word

Official term: Epizeuxis (“eh-pi-ZOOK-zis”)

Much like the above literary device for repeating phrases, this device is a bit simpler: Just one word.

Examples:

“Never give in — never, never, never, never, in nothing great or small, large or petty, never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense.”

– Winston Churchill

Repeating the Same Word or Phrase at the Beginning and End of a Sentence

Official name: Epanalepsis (“eh-puh-nuh-LEP-sis”)

Again, similar to the above (so many of these are related, it makes variations really fun), this form of repetition is a bit like an Oreo: Repeated words/phrases are the cookies, other words are the stuffing.

Examples:

“The King is dead. Long live the King!”

Repeating the Same Word or Phrase at the Start of Consecutive Sentences or Clauses

Official name: Anaphora (“ah-NAH-four-uh”)

One of the most famous of these old-tyme literary devices, this is the one made famous and memorable by speeches like Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech (see below).

The effect here, according to Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric, is two-fold: “Returning to the same words creates a hammering effect; and starting sentences with the same words also creates an involving rhythm” which can then be repeated or abandoned.

Examples:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

– Martin Luther King (“I have a dream” is repeated at the start of eight sentences in a row)

“Mad world! Mad kings! Mad composition!”

– William Shakespeare, King John

There also can be a bit of unexpected climax with anaphora, for instance when the repeated phrase leads to a sentence where the repeated feeling gets flipped on its head. For example:

Sir, he was dull in company, dull in his closet, dull everywhere. He was dull in a new way, and that made many people think him GREAT.

– Johnson, in Boswell’s Life (1791)

Repeating the Same Word or Phrase at the End of a Series of Sentences or Clauses

Official name: Epistrophe (“e-pis-tro-phee”)

Here we have the opposite of the anaphora, the device mentioned above, where the repeated word/phrase occurs at the end.

Examples:

Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee.

– Herman Melville, Moby Dick

“What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny compared to what lies within us.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

Repeating Words at the Start of Successive Sentences or Clauses and at the End of Them

Official name: Symploce (sim-plo-see or sim-plo-kee)

Sound familiar? Symploce is a combination of anaphora and epistrophe—repeated words/phrases at the beginning and end of a clause. As you’ll see in the examples below, the repetition is nearly fully exact, which makes for a memorable turn of phrase.

Examples:

I am not afraid of you; – but I am afraid for you.

– Anthony Trollope, The Prime Minister

The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.

– G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

A Note About Abandonment

A number these literary devices have a touch of rhythm to them, which is one of the great aspects of what makes them so memorable and catchy.

By the same token, there’s something to be said for abandoning this rhythm right at the point when the reader thinks they know what’s coming next. Abandonment often makes for good humor also, as the unexpected catches people off guard in a fun way.

And now for some fun ways to put it all together.

These exercises can help with getting in the mindset to use your best words, sentences, and paragraphs to get your point across. Some might be great for brainstorming new ideas; some might be great for coming up with the text you’ll share on Facebook or Twitter.

Escalator Pitch

You’ve maybe heard of an elevator pitch? A pitch you can make in the time it takes to ride an elevator with a prospective buyer?

The escalator pitch is similar, with a twist.

Instead of a pitch that lasts as long as an escalator ride, the escalator pitch isa pitch short enough that you can make it on your way up the escalator as your potential buyer is on his/her way down.

Example:

High-Concept Pitch

One step beyond (shorter) than the escalator pitch is the high-concept pitch. Think: Hollywood movie taglines.

The high-concept pitch originated in Hollywood, where producers would pitch studio executives with the catchiest, quickest summary possible.

The high-concept pitch is an extremely short phrase, encapsulating an idea by comparing it to another idea.

Example:

- Alien is “Jaws in space.”

- The Uber of workouts

- The Birchbox of …

Micromessage

Christopher Johnson’s book Microstyle explores this idea of micromessage—an idea that is likely familiar to all of us who share to social media. Christopher defines a micromessage as:

Using simple elements to maximum effect

To carry it forward, this could include most any of the literary devices, syntax, and style that we’ve discussed so far in this article. The goal—be it in a tagline, a tweet, a headline, or an advertisement—is to get noticed and communicate quickly.

Examples:

The Edgar Wallace Plot Wheel

A novelist in the 1920s, Wallace patented what he termed as a plot wheel, a literal wheel that he would spin whenever he was stuck for a plot or advancement to his story.

Though his exact wheel is a bit hard to come by these days, a few others have remained. Erle Stanley Gardner, another early 1900s novelist, had a series of wheels to help with plot development in his novels. Here’s a taste,courtesy of Karen Woodward:

The Wheel of Hostile Minor Characters Whose Function is Making Complications for the Hero

These folks put obstacles in the hero’s way, make it difficult for her to reach her goal.

- Hick detective

- Attorney

- Newspaper reporter

- Detective

- Business rival

- Rival in love

- Father of heroine

- Blackmailer

- Gossip

- Meddlesome friend

- Suspicious servant

- Hostile dog

- Spy

- Incidental crook

- Hotel detective

- Thickheaded police

Solution Wheel

How the hero surmounts the obstacles thrown in his way.

- Gets villain to betray himself through greed.

- Gets the villain to, of his own free will, plant additional evidence.

- Plants fake evidence to confuse the villain.

- Fakes circumstances so the villain will think he/she has been discovered.

- Tricks the hero’s accomplice into confessing.

- Villain is hoist by his/her own petard.

- Villain killed while he/she is trying to frame someone.

- Gets villain to overreach himself/herself.

- Meets trickery with horse-sense.

- Squashes obstacles by sheer courage.

- Turns villains against each other.

- Traps [tricks?] villain into betraying a hiding place. Hero either a) creates a fake fire, or b) gives him/her something else to conceal, or c) makes it necessary for the villain to flee (and so must take something out of the hiding place).

There’s also The Wheel of Complicating Circumstances and The Wheel of Blind Trials by Which the Hero is Mislead or Confused, both of which you can read at Karen’s blog.

Similar tools exist today for inspiration with headlines and blog posts.

Incubation Method

A favorite of F.L. Lucas (author of Style: The Art of Writing Well), this method is one that we’ve employed to good results here at Buffer also, building bits of it into our editorial process.

- Stage 1: Meditation and documentation.

- Stage 2: Incubation.

Here’s a bit more from F.L. on his incubation stage:

Periods of alternate thought, quick writing, and partial revision, till the first draft is complete. Revision; further documentation, correction, curtailment, and amplification. This can be repeated indefinitely, subject to the danger of the book [article] growing unwieldy, overloaded, or stale.

Kicking the Geese out of the Boat

This is a fun and quick one, best saved for the revision process.

Writer Alfred Tennyson had a part of his editing process that he dubbed “kicking the geese out of the boat.” It worked like this:

Avoiding the juxtaposition of a word ending with ‘s’ and a following word beginning with it.

Example:

Change: “Do your updates seem flat? Try on a literary device!” to: “Do your updates fall flat? Try on a literary device!”

A Final Note About Clarity and Obscurity

One should not aim at being possible to understand, but at beingimpossible to misunderstand.

– Quintillian

All this amazing info on syntax and style and rhetoric and linguistics is bound to make your social media updates shine. At the same time, there might just be a limit to having too much of a good thing.

One of the most essential elements of good writing (for the web, for books, for anywhere really) is clarity and brevity.

In the Quintillian quote above, this point is highlighted wonderfully. The goal should always be that your audience understands what you’re writing—and if that means using simpler words and phrases and leaving out a cool syntax or two, then so be it.

Where clarity and brevity fail, obscurity thrives. F.L. Lucas has a really great take on where obscurity tends to come from so often:

… Most obscurity, I suspect, comes not so much from incompetence as from ambition – the ambition to be admired for depth of sense, or pomp of sound, or wealth of ornament.

It is for the writer to think and rethink his ideas till they are clear; to put them in a clear order; to prefer (other things equal, and subject to the law of variety) short words, sentences, and paragraphs; not to try to say too many things at once; to eschew irrelevances; and, above all, to put himself with imaginative sympathy in his reader’s place.

Obscurity arises

- By saying too many things at once (a lack of clarity and brevity)

- Having too many ideas and not enough sense of what’s relevant

- When trying to impress people

- By using flowery language when shorter words would do just as well

Over to You

Which of these literary devices and linguistic approaches are you most excited to try?

Which are you already using? Which ones are working?

I’ve got a number of these set up to test in my Buffer queue right now and am excited to see the results. If you get a chance to try any of these on, please do report back here in the comments. It’d be amazing to hear from you!

This post originally appeared on Buffer, and is re-published with permission.

Source – SearchEngineJournal.com